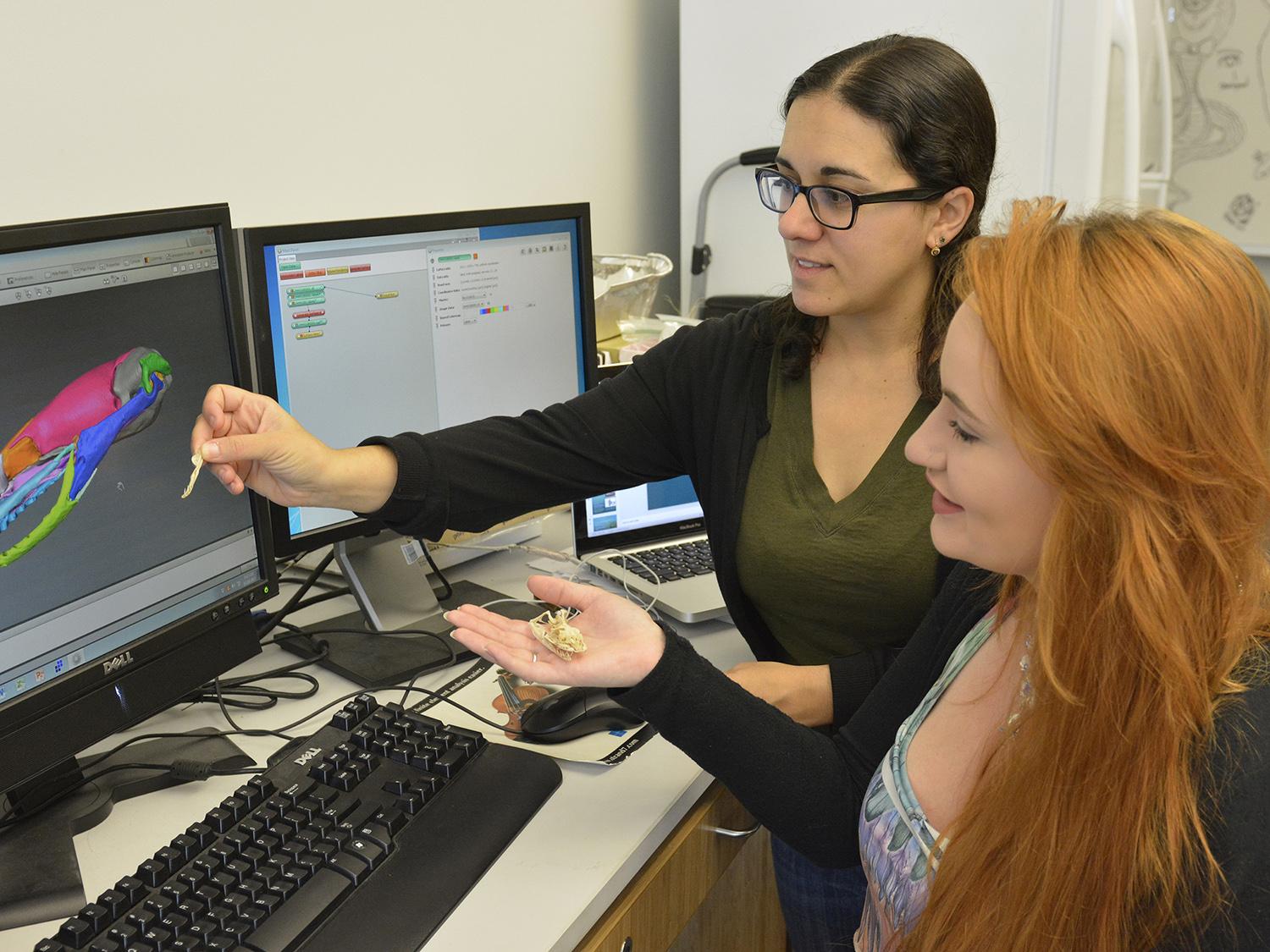

Skull session -- SUNY Oswego zoology major Meghan Gillen (right) observes -- in hand and on the computer screen -- the skull shape and structure of specimens of the Uropeltidae family of burrowing snakes, as part of her training with biological sciences faculty member Dr. Jennifer Olori, who recently won a National Science Foundation grant to examine evolution of limblessness and head-first burrowing in extinct species.

Dr. Jennifer Olori of the biological sciences faculty recently won a National Science Foundation grant for a project designed to provide undergraduates -- particularly women, who remain underrepresented in sciences and math -- with research experiences focused on head-first burrowing animals from as long ago as 300 million years.

Thanks to the $73,165 grant from the NSF's Division of Environmental Biology, the project promises to provide students with training and skillsets applicable to such disciplines as paleobiology, comparative anatomy, computer science, computational analysis and even robotics.

Titled "Repeated evolution of limblessness and head-first burrowing in tetrapods: Testing predictions from the fossil record," SUNY Oswego's grant is part of a collaborative project spanning universities, research specialties, and student assistants in graduate and undergraduate programs.

"Tetrapod" means "four feet," not only referring to the four-footed animals of today, but also to those that science has shown descended from the last common ancestor of amphibians, reptiles and mammals. Snakes, for example, are classified as tetrapods.

Olori specializes in extinct tetrapods from as long as 300 million years ago, some of which evolved a different form of locomotion. Her project aims to test fossilized animals for skull shape and other characteristics that point to environmental pressures leading to the evolution of limblessness and head-first burrowing. CT scans of skulls from a group of snakes that still exists in India and Sri Lanka will help provide anatomical comparisons.

"There's a lot of opportunity for student work," said Olori, who recently began training one of several women undergraduates who will assist this spring. "The cool thing about this project is not only that it intersects with different biological ideas, but it combines computational skills -- a bit of math skills, a bit of computer science along with biology -- so it very rapidly helps them expand their STEM skills in general. That will help them be more marketable for getting into grad schools and getting jobs."

Visualization software

Part of the training involves learning Avizo, relatively complex software for 3D data visualization and analysis for medical science and industry. Zoology major Meghan Gillen has a leg up on the training -- she already has a SUNY Oswego degree in studio art with an illustration emphasis and is no stranger to feature-rich software and visualization.

Gillen, a Hannibal resident who has published children's books, said the new skills she learns on this project should transfer to her hoped-for career. "I'm very interested in marine environments, endangered coral reefs, fish and other creatures dependent on them, and the evolution of fish. I hope someday to work … to preserve what's left of the reefs."

Meanwhile, a former graduate school colleague of Olori's, Dr. Michelle Stocker at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, works in paleontology with reptiles, some of which burrow with their heads. Stocker won a companion grant for her work, which will include doctoral and other graduate students. Another participant in the project is Dr. Hillary C. Maddin of Carleton University in Ottawa, whose specialty is a group of limbless, serpentine amphibians. All three paleontologists have been working with head-first burrowers.

"We thought, 'So why not join forces and answer a broader question: Why are they all ending up with this head shape?'" said Olori. "Hillary has the developmental expertise. I was already working on biomechanics. Michelle does a lot with family trees of reptile relationships. We wondered, 'What's driving this head shape in the living creatures?'"

'Mostly men'

The idea for a collaborative project boosting women and other minorities in STEM moved to a formal proposal in 2016 and was approved by the NSF earlier this year.

"Coming up in paleontology, there are more and more women participating, but it's still a place where you see mostly men in the higher positions," Olori said. "We wanted to encourage more participation from underrepresented groups."

The researchers also aim to do public outreach, perhaps by means of podcasts.

"We will get an idea of how the skulls are structured and how that's related to the way that they're digging burrows," Olori said. "It's a nice way to get younger students involved, because you can talk about how biology can be used as a model for the way that humans design their own applications, like if we were going to design a robot that digs, or how the skull is structured to withstand forces. So we could also use our project to get students interested in robotics or engineering or even architecture, to some degree."