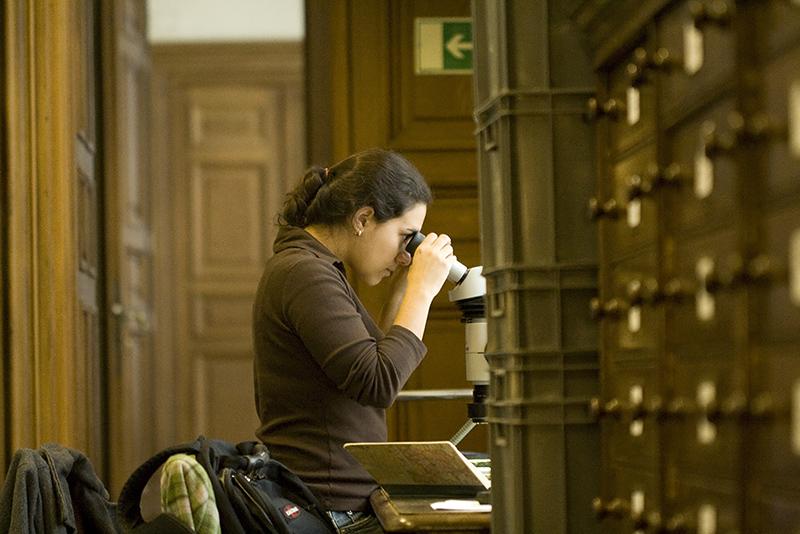

Fossil findings—Dr. Jennifer Olori, a member of the biological sciences faculty at SUNY Oswego, examines fossils of extinct tetrapods at the Natural History Museum in Vienna during a study whose results are reported in the journal Nature. The research team found patterns in the fossil record to suggest regeneration of limbs was a feature of the common ancestor of amphibians, reptiles and mammals, including humans.

Dr. Jennifer Olori of SUNY Oswego’s biological sciences faculty co-authored research published Oct. 26 in the international journal Nature suggesting that regeneration of limbs, unique in modern salamanders, may have been a widespread feature that other four-legged vertebrates lost in the course of evolution.

“From our work it looks like the common ancestor of amphibians, reptiles and mammals had regenerative capabilities, and that the capability subsequently was lost during the history of certain groups, particularly mammals,” said Olori, a co-author to the study’s lead author, Dr. Nadia Frobisch of the Museum fur Naturkunde Berlin.

“However,” Olori continued, “the previously wider distribution of the trait among tetrapods means that researchers interested in identifying regeneration genes or developmental pathways now have more target animals and groups for investigation. Because humans are members of the tetrapod group, regeneration was a part of our very distant past.”

The team of paleontologists from the Berlin museum, SUNY Oswego and Brown University showed that different extinct groups were able to regenerate lost legs and tails in a way exclusively known in modern salamanders—repeatedly and throughout their lifespan.

Classically, the high regenerative capacities of salamanders—recreating entire new limbs as well as organs and tails that include the vertebrae, nerve and muscle—were considered something special and derived for salamanders.

A unique feature of salamanders is that—contrary to other tetrapods, from frogs to humans—they develop their fingers in reverse order. Some have thought this trait might be connected with regeneration. The research team showed otherwise in their new study.

“We were able to show salamander-like regenerative capacities in both (groups)—fossil groups that develop their limbs like the majority of modern four-legged vertebrates, as well as in groups with the reversed pattern of limb development seen in modern salamanders,” Olori said.

The fossil tetrapods used in the study derive from the collections of a number of natural history museums, among them the one in Berlin. Specimens dated from the Carboniferous and Permian periods some 300 million years ago.

Frobisch said the new findings might be of interest in human biomedical studies aiming to unravel the mechanisms responsible for regeneration in salamanders. It may be, she said, that all land animals carry regenerative mechanisms within them due to their common evolutionary heritage.

The Nature article is titled “Deep-Time Evolution of Regeneration and Preaxial Polarity in Tetrapod Limb Development.”