In spring 2025, Penfield Library’s Archives and Special Collections finished digitizing and providing basic metadata for their entire collection of former U.S. President Millard Fillmore’s papers. This marks the culmination of nearly seven years of effort on the part of an evolving team of librarians, staff, and students.

More information on Millard Fillmore and what’s included in this collection can be found in a previous Oswego Today article -- but what exactly goes into a seven-year digitization project?

Librarian Kathryn Johns-Masten began the digitization process for this one-of-a-kind collection back in 2018, when she applied for and received a Special Collections Grant from the Northern New York Library Network (NNYLN). NNYLN is one of nine regional library councils in the state of New York, and it has a mission of supporting member libraries in its territory with resources and services. In this particular case, NNYLN grant money was used to purchase the scanning equipment necessary to digitize archival materials, including the Millard Fillmore Papers.

“The Millard Fillmore Papers are one of several collections held by the library that were identified as being of historical importance,” Johns-Masten said, adding that these are “unique collections that tell a story about our collective history.”

“Over the past six years, librarians, staff and students have scanned, organized and described around 40,000 pages of mostly incoming correspondence addressed to Fillmore,” said Digital Collections Librarian Marissa Caico, who oversaw the completion of the project.

A digitization project as large as this one begins with an inventory of the materials to be imaged so that progress can be tracked, enabling multiple people to work at once and pick up where the last person left off. Next comes the actual imaging, which in this case used an overhead camera setup. Workers placed each page of each document under a piece of plate glass while it was photographed to keep the paper flat and ensure legibility of the scan.

As the images were captured, workers checked each image for quality -- it is important that each one is as close to the original as possible -- ensuring that the document is oriented correctly, in focus and readable. Each scan produces a large image file for preservation and a smaller image file for display and sharing. To keep the massive number of files organized, workers placed files into subfolders according to the year the letter was written.

Once all of the digital files were created and placed in their appropriate subfolders, each letter needed a description. The description of each document provides it with metadata, or information about the document, to help users locate what they’re looking for.

Making the metadata

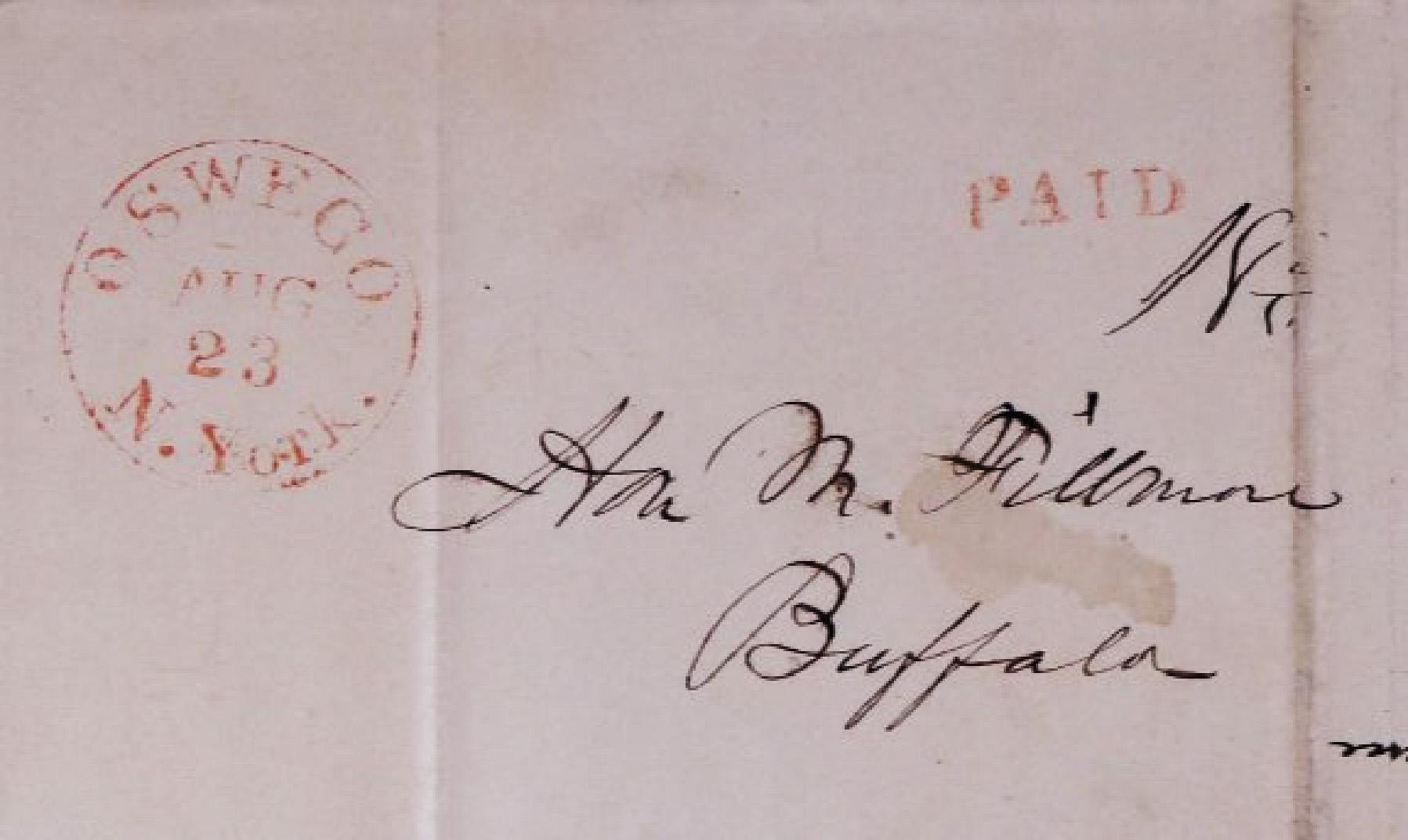

For this project, metadata included simple information like who wrote the document, to whom the letter was sent, and when and where it was written. Library employees and interns had to read enough of each letter to pull that information out and make it available to users. This step makes the collection exponentially more useful to researchers who need to be able to search for a specific person, place or year relevant to their study –- all things that would be impossible to do if library employees didn’t create the necessary metadata.

While creating that descriptive information may seem like a simple enough process, in practice, it can be incredibly challenging.

“Extracting even that small amount of information from the letters was a painstaking process that required the person writing the description to read 19th-century handwriting from various senders,” Caico said. “Having to read unusual handwriting from one person becomes easier over time as you get used to that person's conventions, but this collection is so varied you’re challenged with different hands almost constantly.”

There are letters from hundreds of people included in the Millard Fillmore Papers Collection, and those letters were sent over a period of more than 50 years. Deciphering all that varying handwriting “can be extremely difficult and sometimes frustrating, especially because we are aiming to be as accurate as possible,” Caico said.

Readers who are up for a challenge may enjoy trying to decipher the handwriting of Nathaniel K. Hall, Fillmore’s longtime friend and law partner.

Archives and Special Collections Assistant Austin Richardson was among the library employees faced with this daunting task.

“At first reading, the handwriting was really tough,” Richardson said. “I thought it was going to be like reading cursive in school, but it wasn’t like that at all. It was really frustrating.”

He spent hours working on describing the letters. “Over time, it got easier,” he said. Eventually, he even began to recognize regular correspondents from their handwriting.

Archives and Special Collections intern Molly Metcalf (’24) agreed, saying that “learning 19th-century handwriting was an extremely tough process, but, as you practice more and more, it becomes fun and rewarding.”

Despite challenges, Metcalf noted that she learned a lot about history in the process. “Getting into Dorothea Dix and Fillmore’s friendship was a huge part of this project for me, as I learned more about how mental health care came to be. These two individuals have had more of an impact than the general public realizes.”

'All hands on deck'

University Archivist Librarian Zachary Vickery was another collaborator on this project. Vickery noted his sense of pride in his contributions, as well as pride in the entire team of employees and interns who worked on the project over the years. He also highlighted the importance of everyone pulling together to work as a team.

“With a big project like this, it becomes an ‘all hands on deck’ situation,” Vickery said. “Read the handwriting. Operate the digital camera. Perform quality control. We all learned how to do these things, and as a result, we all grew our professional skills.”

Going forward, Caico says she’d like to improve the searchability of letters in this collection. Efforts to achieve this are already in their early stages. In the spring 2025 semester, intern Yashaswi Shrestha (’25) worked on a mapping project using the Fillmore letters in ArcGIS to make their locations more discoverable.

Caico said she’d like to be able to provide a searchable full text of each letter and also pull out important topics from letters to include as keywords in their metadata.

“Archives and Special Collections intern Molly Metcalf and student assistant Julianne Saunders (’25) experimented with the AI tool Transkribus for handwritten text recognition,” Caico said. Using Trankribus requires producing transcriptions manually and then using those transcriptions to train an AI model.

Metcalf and Saunders worked with letters from Dix, a social reformer and friend of Millard Fillmore, who had notoriously difficult handwriting to read. Their goal was to use those transcriptions to train a model in Transkribus, though they ran into difficulties from time limitations and the challenge of manually transcribing enough of Dix’s handwriting with enough accuracy to train the AI on.

“The handwritten text-recognition capabilities of AI tools in general really vary when it comes to historical examples,” Caico said. “Experimenting with these tools on unique collections presents important opportunities to engage with new technologies and think about both the practical and ethical considerations of using these technologies with archival materials.”

In addition to all the other efforts being made to transcribe these letters, Caico wants to hold an event to open the task up for any interested students.

“I’m hoping to organize a transcribe-a-thon,” Caico said. “Being able to transcribe the letters at a mass scale would be really beneficial for us.” The date and details of that event are still to be determined, but all Penfield Library events are promoted on the library homepage and the SUNY Oswego Events Calendar. Anyone interested in that event should keep an eye out for more information coming soon.

-- Submitted by Penfield Library