Breakthrough research -- Daniel Baldassarre, a current SUNY Oswego biological science faculty member, recently published research that found the phainopepla is only the third kind of bird with a particular and peculiar migration pattern.

Research from Daniel Baldassarre, a current SUNY Oswego biological sciences faculty member, found only the third kind of bird with a particular and peculiar migration pattern -- which captured widespread attention and opens the door to even more research on migratory behavior.

Baldassarre’s breakthrough research on the phainopepla confirmed its rare itinerant breeding activities, or that it nested in one area, migrated and then nested again. Published in The Auk: Ornithological Advances -- a peer-reviewed, international journal of ornithology published by the American Ornithological Society -- the research was picked up by several scientific media outlets, including that of the National Audubon Society.

Scientists had known that populations of phainopepla breed in the desert in spring and in the woodlands in the summer, but that these were the same birds following an unusual migration pattern had never been proven before Baldassarre’s work.

Many birders, natural historians and photographers had wondered about this “weird species” in the southwestern United States, said Baldassarre, who made this research a focus while in a postdoctoral position at Princeton University.

“We looked at the genetic attributes of these populations of birds -- asking whether they came from the same gene pool or were genetically different,” said Baldassarre, noting the collaborative part of the study used DNA samples from others who had studied the species. But finding a way to prove the birds actually traveled and bred in both places was the missing piece of the puzzle.

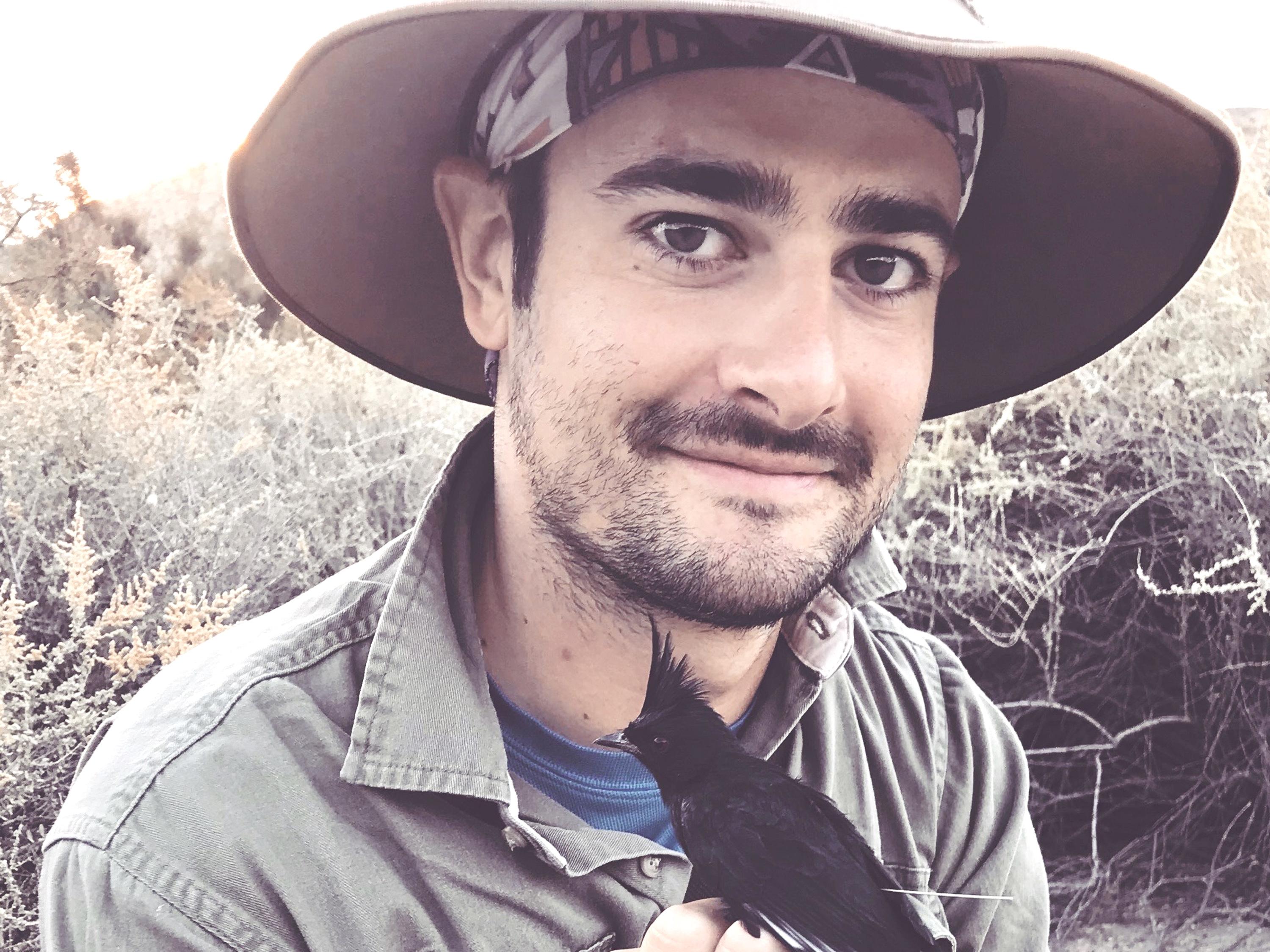

“What I contributed was new data collection by trying to directly track the birds,” Baldassarre said. This involved capturing them, then marking and equipping them with a small GPS tracker that weighs only a gram. The tracking data was only available by collecting and downloading the information, so he would have to catch what he hoped were returning birds and retrieve details on their travels.

“Seeing the GPS tracks for the first time was amazing, but the biggest thrill for me was re-sighting the first tagged bird that returned to the capture site,” Baldassarre said. “We were a bit unsure how likely they were to come back to the same spot, so to see that a tagged bird had returned was an exhilarating moment.”

Only two other species are known to have these kinds of behaviors, but Baldassarre’s success and the improvements in tracking technology opens the door to other researchers using similar techniques to see if more birds follow these patterns.

“We may be underappreciating how flexible birds are in doing this through the year. In light of climate change, that can potentially benefit some species of birds,” Baldassarre said. “It was fun trying to crack this case, to figure out if these birds were a rare phenomenon.”

New research

Since coming to Oswego, a primary research project he has begun with students involves studying the adaptability of cardinals, a species that is very common and well-known to humans -- and that seems to adapt well around human activity.

“They seem to deal with change very well. They go into people’s backyards, use bird feeders and show up in city parks,” Baldassarre said. The questions he and his students are exploring include: “What makes them so flexible? Are they particularly smart? Maybe they deal with stress better. Maybe they’re bolder. Maybe they’re less afraid of humans.”

The research group is studying two different populations: one in Rice Creek Field Station and one in Barry Park in Syracuse. “It’s a nice comparison of populations from the same species, one that’s in a more pristine environment in Rice Creek, one that’s in a city park, and how humans affect them,” he said.

Like the research that earned the attention of so many scientists and birders, Baldassarre again compared it to trying to crack a code. “I think we take for granted what they’re capable of,” he said of the cardinals, “and how they are able to co-exist with us so well is an interesting question.”

Baldassarre joined Oswego’s faculty in 2018, as he and his wife both hail from Central New York, but the position also attracted him because of what the college offers faculty and students.

“I just really like the idea of working at a place that is student-focused, and I really like teaching,” Baldassarre said. “There’s a really nice balance in allowing faculty to do meaningful research as well as teach."