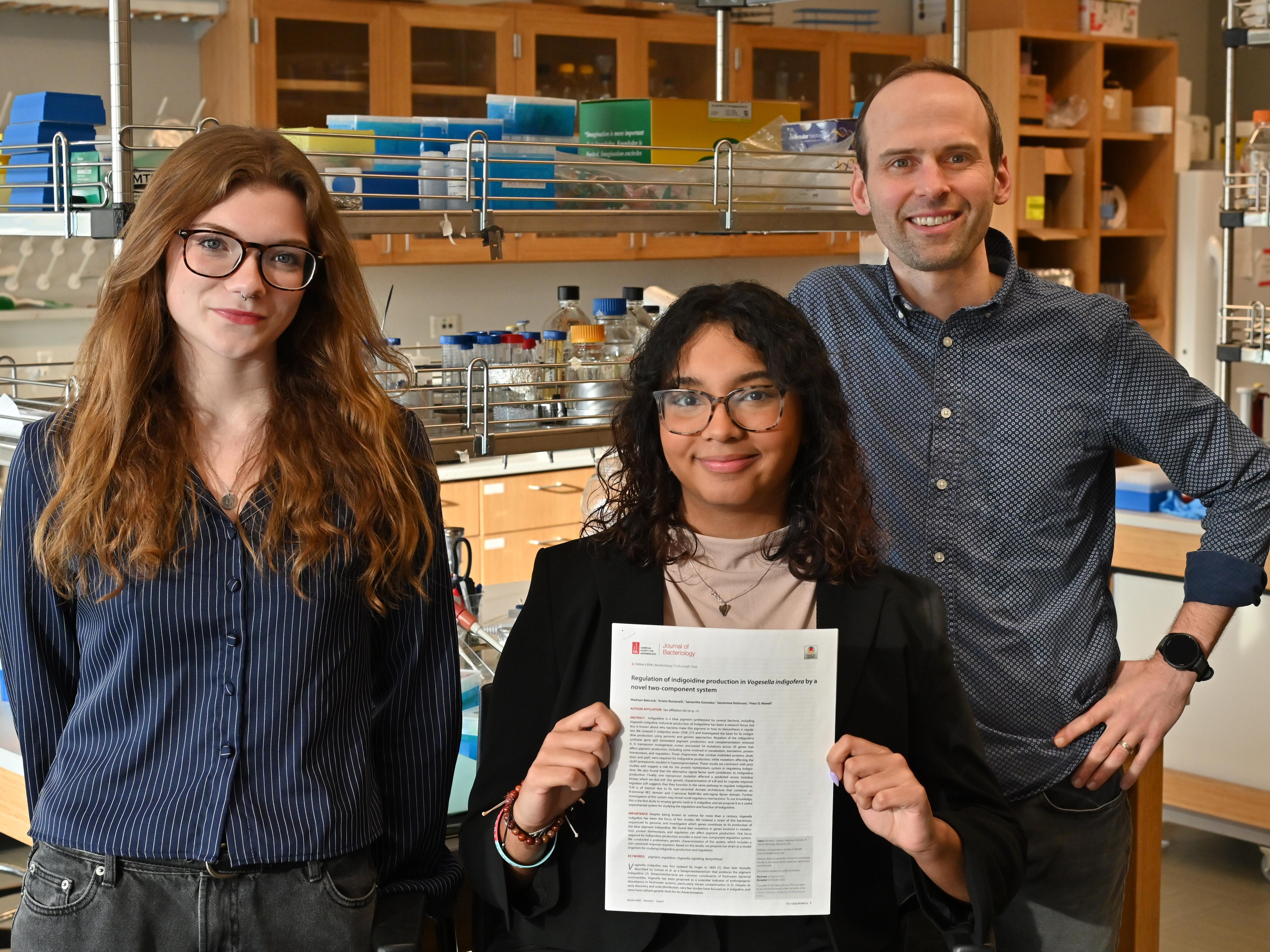

Peter Newell of the Biological Sciences Department and student researchers recently published their groundbreaking work with a unique bacterial species known as vogesella indigofera in the Journal of Bacteriology. From left are student researchers Genevieve Robinson and Samantha Gonzalez with Newell. Other co-authors who have since graduated are Madison Babcock and Kristin Romanelli.

What began as an outreach event for elementary schoolchildren turned into an opportunity for biological sciences faculty member Peter Newell and his students to break new ground in microbiology research.

The discovery of a unique regulatory system in the bacterial species vogesella indigofera and the ongoing exploration by Newell and his students resulted in a paper published in December in the Journal of Bacteriology.

“Regulation of indigoidine production in Vogesella indigofera by a novel two-component system” featured student authors Madison Babcock, Kristin Romanelli, Samantha Gonzalez and Genevieve Robinson joining Newell.

The research project was a byproduct of serving the community and curiosity. During a science open house for local schoolchildren in the Shineman Center, an outreach program supported by the Shineman Foundation, Newell was presenting some samples of cells and microorganisms, “things that are alive but too small to see without a microscope,” he recalled.

“This one particular colony on the petri plate was bright blue,” Newell said. “An elementary school student pointed and asked why it was blue. It was a great question.

“I sampled microorganisms from different environments to show the diversity of microbial life,” Newell said. “This particular sample came from down on the lakeshore in some water runoff, where you can find a diversity of aquatic microorganisms.”

At that point, around two years ago, “We realized it’s a good organism to study more, and also a good teaching tool, a way to spark interest in bacteria,” Newell said. “As we learned more, we realized there’s something kind of unique here nobody has studied before.”

Newell and the students were surprised to find only a handful of publications on the organism in the modern scientific era, and none that employed modern genetic tools.

“The first study of this organism is from the 1800s, but nobody had used basic genetics to study it, and nobody had published on it,” Newell noted. “This became an opportunity for my students and me to contribute something to this body of scientific knowledge that nobody has taken the time to add.”

They started by sequencing the vogesella genome, to learn what genes it used to make the striking blue pigment, and then discovered an even more unique trait in this microorganism.

“We discovered this new kind of two-component signaling system,” Newell said. “This variation of signaling proteins is unlike anything that we’ve ever seen before. It’s a two-component system that consists of two different proteins, with a sensor sensing some change in the environment –- which could be salt, pH or temperature -- and what’s called a response regulator. The sensor communicates to the regulator, and that causes the regulator to make changes in the cell.”

While two-component regulator systems aren’t unusual in bacteria, “the regulator we discovered has a unique protein structure. Nobody has studied this variant before, and we don’t know what it does yet beyond turning the cells blue.” Newell said.

Proteins in general have modular architecture –- like Legos or building blocks –- all made of different modules, similar to the way Lego sets go together, Newell explained.

“This response regulator combines two blocks nobody’s seen stuck together before,” Newell said. “That leaves an open question as to what this particular tool is used for in the cell. I hope we can figure it out in the next couple of years.”

Learning by doing

These breakthroughs worked hand in hand with a great research opportunity for students that went beyond what everybody initially expected.

“A big part of our philosophy here in the Biological Sciences Department and the college in general is you learn by doing,” Newell said. “Going through all the steps of this scientific process is the only way to develop scientists. It’s important that students see themselves as part of the scientific process.”

A couple of the students developed research reports as their senior theses, so Newell incorporated their writings. “Everybody made contributions in different ways, and they get to see all the aspects of the research along the way,” he noted. It provided an opportunity for them to write in a technical way that the scientific community receives favorably, and also see the levels of corrections and checks that go into publishing in a major journal.

“I’ve been very fortunate in terms of having great students here over the years,” Newell said. “My students come and volunteer to do research, and we get them registered for an independent study. All of the students on this paper have done independent study as part of the work.”

Newell thought back to his own lightbulb moment: How the first time he took a course when he had to design his own experiment, not just follow instructions, really showed him the possibilities –- and he pays that discovery forward for today’s student scientists.

“Basically, all the lab courses I teach involve students developing their own research,” Newell explained. “That really develops their skills more than just conducting experiments somebody else created. They get to think through the process as a new idea.”

Babcock, a December 2024 biology graduate, is currently a research support specialist at SUNY Upstate Medical University’s Department of Pharmacology.

“What really drew me to this research was the opportunity to work on something that was unknown,” Babcock said. “The bacterium we studied hadn’t been well researched, and its blue pigment raised questions about why it was blue, how it is regulated and what role it might play in the environment. I was excited by the idea that we weren’t just following a straight path but actually helping to pioneer new knowledge about vogesella.”

“Many breakthroughs happen on the back of basic science research,” Newell said. “I’m fortunate that I’m able to ask questions about how basic cells work and, by adding to the body of knowledge for molecular biology, you never know what piece of information will lead to some kind of breakthrough or advance.”

Research benefiting students

The participating students benefited from the project in many ways.

“I learned that all areas of science are interconnected,” said Gonzalez, a biology major and chemistry minor. “Solving or asking one fundamental question or problem often leads to many more, ultimately helping us better understand ourselves and the world around us. I also learned that genetics is complex, and that different proteins and genes can work together to carry out a wide range of functions.”

“This project showed me how experimental science works from the ground up –- asking questions, troubleshooting and learning from unexpected results,” Babcock explained. “I also gained a wide range of hands-on laboratory and bioinformatics skills and learned how to think critically about data, which helped me understand what doing real scientific research looks like beyond the classes.”

For Gonzalez, who “came to Oswego with a passion for science and a desire to make a contribution to society,” this opportunity provided opportunities on this path.

“During my freshman year, I took my very first laboratory classes in biology and chemistry, and that was when I realized I had a strong passion for microbiology and genetics lab work,” Gonzalez said. “Having Dr. Newell as my professor and mentor further deepened my appreciation for laboratory research and helped me find even more joy in lab work.”

Robinson, a zoology major, heard about the work from other students and “I was intrigued about microbiology research and taking the class furthered that interest.”

“I learned valuable in-lab skills like, for example, learning how to design my own experiment in detail,” Robinson said. “I was able to strengthen my problem-solving and collaboration skills by working with others to develop experiments and giving each other feedback on our own independent work.”

The trial-and-error process “helped me realize that there is no such thing as a mistake in science,” Gonzalez noted.

“I performed many procedures where I encountered obstacles and learned to view them as learning experiences rather than failures,” Gonzalez said. “This opportunity also allowed me to connect with other peers who share the same passion for science. Additionally, I learned how to present scientific data and explain it clearly to a general audience.”

Romanelli, who earned a biology degree in May 2025, can draw on this experience as a graduate student at Long Island University in the Clinical Laboratory Science program.

As students move forward in their careers, this experience provides them with demonstrable experience as well as established skills.

“My research experience at SUNY Oswego played a major role in preparing me for my next steps after graduation,” Babcock said. “It gave me a strong foundation in experimental design, critical thinking and bench work, which made the transition into my current role as a laboratory technician much smoother. The skills and confidence I gained through my research at Oswego continue to be a key asset in my work today.”