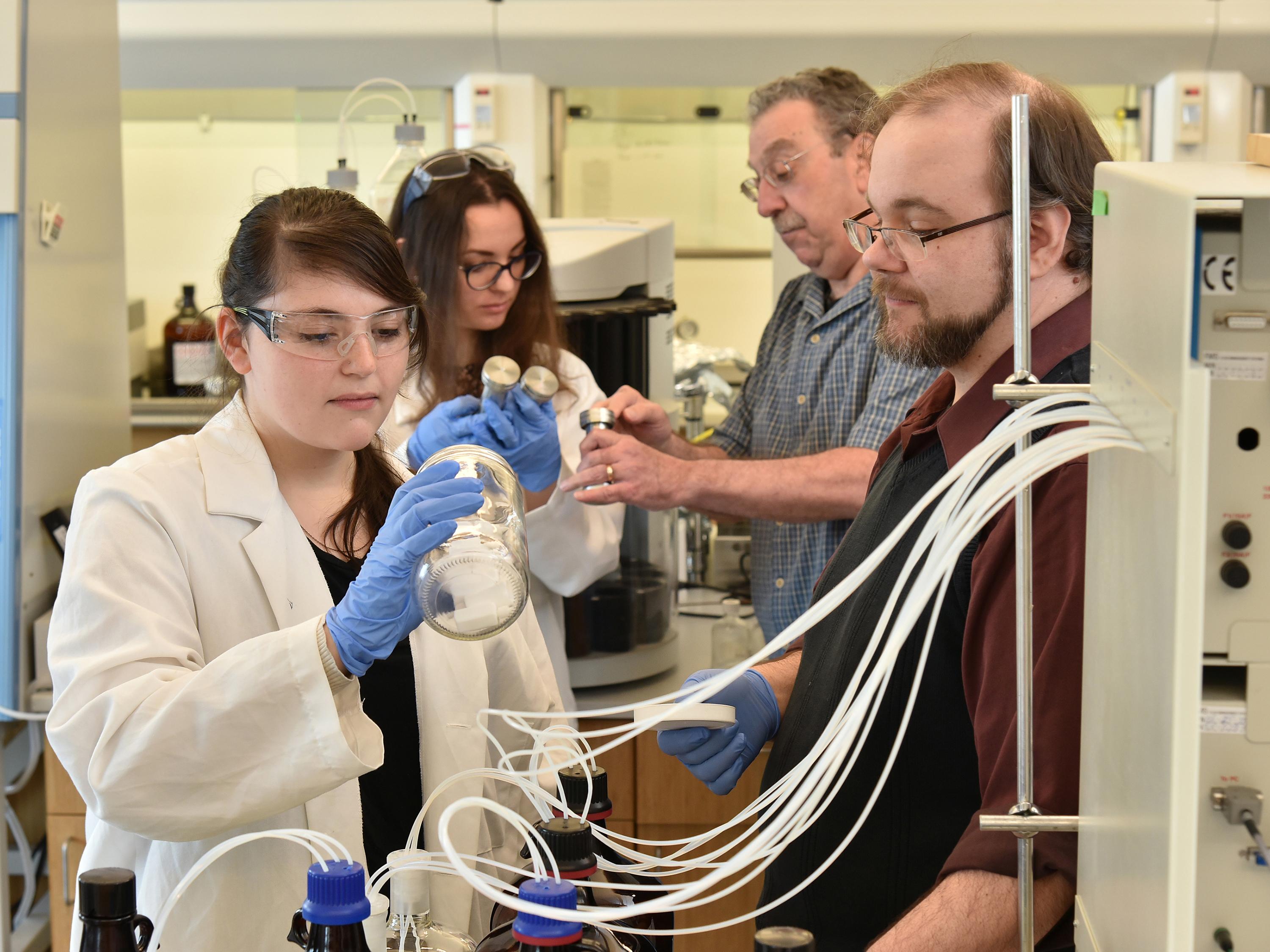

Lake research -- SUNY Oswego and its Environmental Research Center, teaming up with Clarkson University and SUNY Fredonia, are finding Great Lakes contaminant levels experiencing a welcome drop. The colleges collaborate under the ongoing Great Lakes Fish Monitoring and Surveillance Program, funded by U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Shown in the Shineman Center lab, from left, are student researchers Brianne Comstock and Daria Savitskaia; James Pagano, director of the Environmental Research Center; and Andrew Garner, the research associate who manages the lab.

Ongoing research by three New York colleges shows that Great Lakes contaminants continue a welcome and dramatic downward drop, said project investigator James Pagano, director of SUNY Oswego’s Environmental Research Center.

Oswego is a partner with Clarkson University and SUNY Fredonia on a five-year $6.5 million “Great Lakes Fish Monitoring and Surveillance Program: Expanding the Boundaries” project funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The colleges have been collaborating to monitor such persistent toxic chemicals as PCBs, dioxins, furans and other legacy pollutants since 2006.

“Using data from the 1970s and early '80s, and data we’ve collected in the current period, we’ve seen a decline of nearly 90 percent of toxic equivalence in lake trout,” Pagano said. The data in large part reflect federal and state programs, from 1970’s Clean Air Act and 1972’s Clean Water Act to more stringent regulations to dredging to awareness-building campaigns -- a widespread effort to improve the Great Lakes.

The ecology of the Great Lakes is a far-ranging concern as the largest group of freshwater lakes on Earth, nearly 94,000 square miles and supporting a population of nearly 38 million people in the U.S. and Canada, the studies noted. The Great Lakes Fish Monitoring and Surveillance Program began in 1980 to address concerns over the declining state of the lakes and how that impacts the health of those living throughout the region.

The Clarkson-Oswego-Fredonia partnership started on smaller projects in the 1990s, and the current work -- which includes $1.5 million in support for Oswego -- is the third round of five-year funding the three institutions have earned from the EPA.

The most recent grant has allowed the team to expand its list of target chemicals and to try to identify new threats before they become potential problems for fish, other lake inhabitants, wildlife and humans who might consume those fish.

The EPA grant supports SUNY Oswego’s Environmental Research Center, equipped with high-tech instruments on the fourth floor of the Shineman Center, which not only carries out work for this vital research project, but also provides laboratory experiences for students.

Healthier results

The team’s research has most recently appeared in multiple articles in Environmental Science & Technology, with an upcoming piece in the Journal of Great Lakes Research.

“The levels have come down quite a bit,” Pagano said. “The news is really good, for the most part.”

Research associate Andrew Garner has been a member of the Oswego team since 2012, preparing many of the tissue samples, running the ERC lab and serving as co-author of some work, including second author to Pagano on one article in Environmental Science & Technology.

That piece, “Age-Corrected Trends and Toxic Equivalence of PCDD/F and CP-PCBs in Lake Trout and Walleye from the Great Lakes: 2004-2014,” notes that the six contaminants of interest in Lake Ontario lake trout decreased between 45.7 and 55.3 percent -- and most by more than 50 percent -- during the period studied.

But the work comes with challenging parameters. The team learned it had to correct for one unexpected variable: Some fish in the Great Lakes are living longer, and while this is a positive, it also means the average sample can have a higher level of toxins because the animal’s longer lifespan means more time to absorb these compounds.

The EPA vessel Lake Guardian will return to Lake Ontario this summer for a thorough sampling expedition. The ship rotates through the Great Lakes, most recently doing this work on Lake Ontario in 2013.

Other biological sciences faculty at Oswego have key roles in the ongoing project as well. Associate professor James MacKenzie performs toxicology research using liver assays of lake trout, a top predator in Lake Ontario. Professor Richard Back leads a study on contaminants in plankton and other living organisms in the lakebed.

Students on board

Pagano has been able to hire talented students over the years for paid work in the lab, which allows them to benefit from the opportunity to learn and work on such an important project. Some graduates have moved on to professional research positions and doctoral studies.

Senior biochemistry major Brianne Comstock, who has worked in the lab since her junior year, incorporated her activities into her capstone project, “Detection of Dioxin Photoproducts from Triclosan in Biota,” which won a Sigma Xi research award in April for Quest.

“I’m really glad to have the experience of working in a lab environment, and to work with really high-tech instruments,” said Comstock, who next will pursue graduate studies at St. John Fisher’s Wegmans School of Pharmacy. “And the kind of work we do is so applicable and important. … People need to recognize that if they put something down the drain, it does go somewhere.”

Sophomore biochemistry major Daria Savitskaia, in her first semester at the lab, is training to take Comstock’s place. “It’s really important to learn first how the lab operates,” she said. “I’ve learned there are so many small details to keep in mind when you conduct an experiment.”

Even with regulations and higher awareness, and with the valuable work of teams across institutions, the task of cleaning up the Great Lakes is an ongoing one.

“There’s still more we can do,” Pagano noted. “Getting the last 10 percent out of the lake, out of the biota, is going to be hard to do.”

SUNY Oswego, its faculty and its students will look to do their part: The campus selected the global issue of Fresh Water for All as its first cross-campus Grand Challenges project.