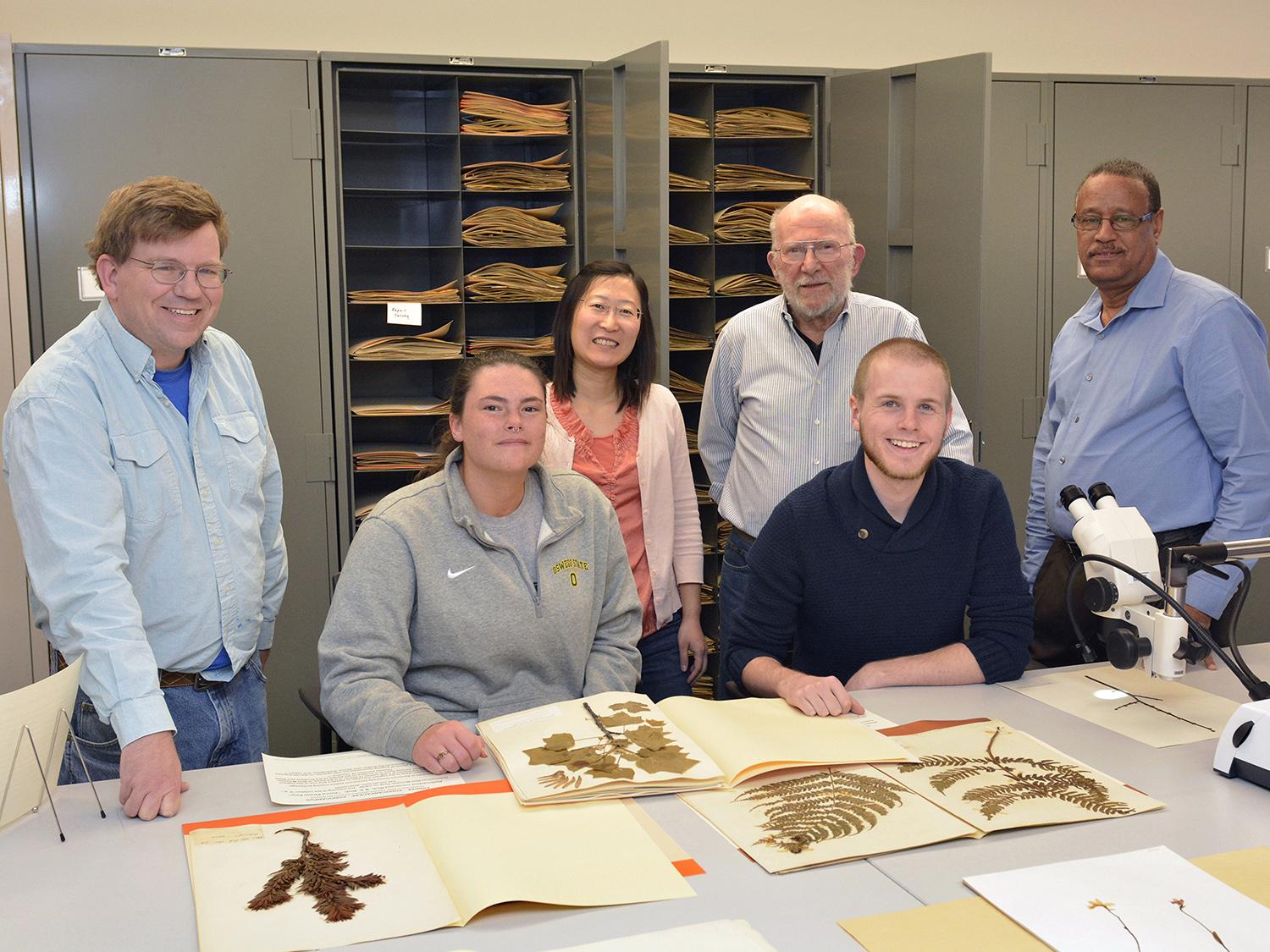

Herbarium team—Among those at a reception in Room 306 of the Shineman Center celebrating the four-year project to restore and index more than 50,000 plant specimens in SUNY Oswego’s collection are (standing from left) biological sciences faculty members Eric Hellquist and Jinyan Guo, project leader and professor emeritus Andrew Nelson and Rice Creek Field Station Director Kamal Mohamed. At the table (from left) are students Sarita Charap and Robert Jarvis, assisting in restoration of damaged specimens.

SUNY Oswego’s recently opened herbarium features more than 50,000 dried and mounted plant specimens in a historically significant collection that links the main campus’ scientific education and research mission with that of Rice Creek Field Station.

The herbarium—with some specimens dating from the first half of the 19th century—opened in December during a celebration of several developments: its space in Room 306 of the Richard S. Shineman Center for Science, Engineering and Innovation; its inclusion on an international registry, Index Herbariorum; and the nearly four years of restoration and reorganization it has taken to ready the plant museum for scientific and public use.

College President Deborah F. Stanley made remarks on the achievement during the reception for biological sciences faculty members—past and present—and students involved in the project to revive and update the herbarium.

Until the Shineman Center was built from 2010-13, the collection resided in the basement of Piez Hall. The bulk of the collection—some 35,000 mounted and labeled specimens plus a quantity of unmounted material—came to the college as a donation from Syracuse University in the mid-1970s. SU over the years had received many contributions from private collections; for example, a specimen of white pine collected in Connecticut in 1840 was on display at the reception.

In fall 2013, SUNY Oswego biological sciences faculty members James MacKenzie, department chair, and Kamal Mohamed, director of Rice Creek, secured the volunteer services of professor emeritus Andrew Nelson, who personally had made many additions to the herbarium collection at the field station. The Rice Creek collection now catalogs plant species growing on Rice Creek’s 400 acres; other collections have been integrated with the vast one on the main campus.

Nelson—Rice Creek’s director for 15 years and an Oswego educator and botanical expert for decades who remains active in the field—has spent two days a week going through the entire collection, updating plant nomenclature and reorganizing the donated collection in large upright cabinets.

Student archivists

For new specimens, the process of preparation has remained unchanged for years, Nelson said: Up to 50 to 60 freshly collected plants are layered into a plant press between sheets of newspaper and cardboard, and dried under mild heat, then mounted on archival paper for notation and indexing.

However, a number of the long-dried specimens in the Shineman Center herbarium had been damaged over the years. Nelson received help last semester from senior zoology major Robert Jarvis, employed by biological sciences faculty member Eric Hellquist under the college’s work-study program, to help restore specimens for cataloging and display. Junior zoology major Sarita Charap plans to work in the herbarium this semester, continuing Jarvis’ painstaking job using special glue and tape in the restorations.

Hellquist, long active in botanical and other research at Rice Creek Field Station and Yellowstone National Park, said his goal is to get students increasingly involved in collecting and preserving Central New York flora. “It’s our job to be good caretakers of the specimens,” he said. “There is good (career-applicable) potential for students in gaining botanical archival skills.”

The next project for Nelson, possibly with student assistance, will be to complete an online database, which would include photographs and as much information as possible about each specimen. While scientists and the public can access the herbarium by arrangement with the biological sciences department, the Internet offers the most reliable way to make the collection accessible moving forward, Nelson said.

Scientific interest

Nelson and Hellquist spoke of a number of specimens and their significance in tracking the evolution and geographic distribution of plant species—including human impacts such as the introduction of invasive species.

“The water hyacinth was likely introduced to the United States at an 1894 agricultural exposition in Louisiana,” Hellquist said. “From there, the invasive species made its way down the St. John River and its watershed to Jacksonville, where our specimen was collected very near the time of its introduction. You can then start to piece together the history of how these plants moved around.”

Nelson said another specimen—Franklinia altamaha, a shrub with white blossoms—came from noted 18th century botanist John Bartram’s own botanical garden. It once grew along the Altamaha River in Georgia, but has been extinct in the wild since about 1803, perpetuated only in cultivation.

Another use of the herbarium is to track the effects of global warming on growing seasons, Hellquist said. For example, data for Trillium grandiflorum, great white trillium or wood lily, show that it used to bloom here in June, he said, but it now blooms in May.

For more information on accessing the herbarium, contact SUNY Oswego’s biological sciences department at 315-312-3031 or biosci@oswego.edu.